Desk Report

Publish: 07 Sep 2023, 01:55 pm

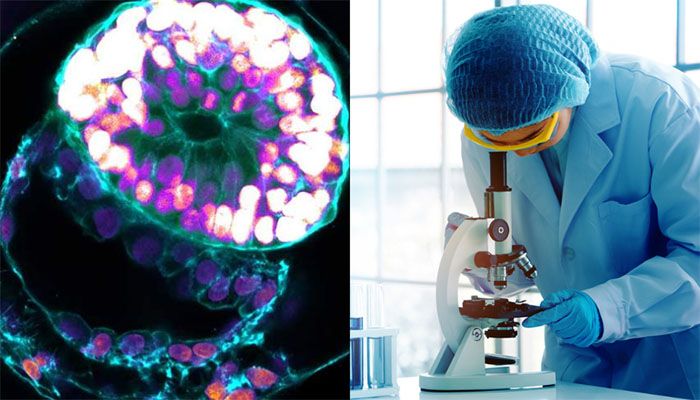

Scientists grow first-ever human embryo model without egg, sperm, or womb || Photo: Collected

Israeli Scientists have grown an entity that closely resembles an early human embryo without using sperm, eggs, or a womb.

The Weizmann Institute team says their "embryo model", made using stem cells, looks like a textbook example of a real 14-day-old embryo.

It even released hormones that turned a pregnancy test positive in the lab.

The ambition of embryo models is to provide an ethical way of understanding the earliest moments of our lives.

The first weeks after a sperm fertilizes an egg is a period of dramatic change—from a collection of indistinct cells to something that eventually becomes recognizable on a baby scan.

This crucial time is a major source of miscarriage and birth defects, but it is poorly understood.

"It's a black box, and that's not a cliche; our knowledge is very limited," Prof. Jacob Hanna, from the Weizmann Institute of Science, tells me.

Starting material

Embryo research is legally, ethically, and technically fraught. But there is now a rapidly developing field mimicking natural embryonic development.

This research, published in the journal Nature, is described by the Israeli team as the first "complete" embryo model for mimicking all the key structures that emerge in the early embryo.

"This is really a textbook image of a human day-14 embryo," Prof Hanna says, which "hasn't been done before".

Instead of a sperm and egg, the starting material was naive stem cells, which were reprogrammed to have the potential to become any type of tissue in the body.

Chemicals were then used to coax these stem cells into becoming four types of cells found in the earliest stages of the human embryo:

A total of 120 of these cells were mixed in a precise ratio, and then the scientists stepped back and watched.

How the embryo was made

About 1% of the mixture began the journey of spontaneously assembling itself into a structure that resembles but is not identical to, a human embryo.

"I give great credit to the cells - you have to bring the right mix and have the right environment, and it just takes off," Prof. Hanna says. "That's an amazing phenomenon."

The embryo models were allowed to grow and develop until they were comparable to an embryo 14 days after fertilization. In many countries, this is the legal cutoff for normal embryo research.

Despite the late-night video call, I can hear the passion as Prof. Hanna gives me a 3D tour of the "exquisitely fine architecture" of the embryo model.

I can see the trophoblast, which would normally become the placenta, enveloping the embryo. It includes the cavities - called lacunae, that fill with the mother's blood to transfer nutrients to the baby.

There is a yolk sac, which has some of the roles of the liver and kidneys, and a bilaminar embryonic disc - one of the key hallmarks of this stage of embryonic development.

'Making sense'

The hope is embryo models can help scientists explain how different types of cells emerge, witness the earliest steps in building the body's organs, or understand inherited or genetic diseases.

Already, this study shows other parts of the embryo will not form unless the early placenta cells can surround them.

There is even talk of improving in vitro fertilization (IVF) success rates by helping to understand why some embryos fail or using the models to test whether medicines are safe during pregnancy.

Prof Robin Lovell Badge, who researches embryo development at the Francis Crick Institute, tells me these embryo models "do look pretty good" and "do look pretty normal".

"I think it's good, I think it's done very well, it's all making sense, and I'm pretty impressed with it," he says.

But the current 99% failure rate would need to be improved, he adds. It would be hard to understand what was going wrong in miscarriage or infertility if the model failed to assemble itself most of the time.

Legally distinct

The work also raises the question of whether embryonic development could be mimicked past the 14-day stage.

This would not be illegal, even in the UK, as embryo models are legally distinct from embryos.

"Some will welcome this - but others won't like it," Prof. Lovell-Badge says.

And the closer these models come to an actual embryo, the more ethical questions they raise.

They are not normal human embryos, they're embryo models, but they're very close to them.

"So should you regulate them in the same way as a normal human embryo, or can you be a bit more relaxed about how they're treated?"

Prof. Alfonso Martinez Arias, from the Department of Experimental and Health Sciences at Pompeu Fabra University, said it was "a most important piece of research".

"The work has, for the first time, achieved a faithful construction of the complete structure [of a human embryo] from stem cells" in the lab, "thus opening the door for studies of the events that lead to the formation of the human body plan," he said.

The researchers stress that it would be unethical, illegal, and actually impossible to achieve a pregnancy using these embryo models - assembling the 120 cells together goes beyond the point at which an embryo could successfully implant into the lining of the womb._BBC

Subscribe Shampratik Deshkal Youtube Channel

Topic : Israeli Scientists human embryo sperm eggs womb

© 2024 Shampratik Deshkal All Rights Reserved. Design & Developed By Root Soft Bangladesh